Mitigating cyber risks in the water and wastewater sector

Mitigating cyber risks in the water and wastewater sector

The past two years have seen an increase in the number and sophistication of cyber-attacks, creating a significant rise in cyber risk for many companies. As the February 2021 attack on a water treatment plant in Florida demonstrated, the water and wastewater sector is not exempt from attacks, which could have potentially severe consequences for society and the economy.

With the vulnerability of critical infrastructure to cyber threats becoming a big concern, the water and wastewater industry is increasing its focus on improving IT infrastructure and developing and training employees to mitigate cyber risks, according to Mazars’ US Water Industry Outlook 2021.

Based on a survey conducted in 2020/2021, the outlook captures the perspectives of different stakeholders, including water and wastewater systems operators, procurement and other support for water and wastewater companies, government regulators and the investment community.

Paul Truitt, Principal, Cybersecurity, discusses the new threat environment and how organisations can mitigate cyber risks to prevent future attacks.

The following is an extract from the 2021 US Water Industry Outlook which can be downloaded here.

Over the past two years, what has changed in the cyber world, are risks higher and are there any new risks?

The most significant change I have seen in the last two years is the type of attacks that have occurred. The Solarwinds attack in Q4 2020 resulted in data breaches in many organisations running the Orion platform created a shift in mindset on where risk may exist. While this type of supply chain attack isn’t entirely new, it is the first time we have seen such a significant impact on both the public and private sectors from a software vendor being breached. This changes the game in terms of an organisation’s risk posture. While we have seen third-party attacks create significant impact like the Target breach from an HVAC vendor, an attack that is entirely outside the control of an organisation and likely not identified as a risk creates a new entry point into highly controlled environments.

The other major attack vector that has significantly changed is ransomware. We have seen these types of attacks in the past as well, with a similar approach to what we see today, starting with a phishing attack. What has changed is the frequency, sophistication and patience of the attacker.

We are seeing ransomware attacks happen nearly every day, and big breaches hit the news every couple of weeks. Preparing an organisation to identify a phishing email was much easier in the past, as there were many telltale signs such as poor grammar, unrealistic claims, or other easy to spot characteristics in an email trying to lure the employee to click a link. The new attacks are very well written, with research about the organisation and are extremely difficult to differentiate from legitimate emails. Many times they include information about a project with real people’s names included to make it feel like an internal message. We are also seeing these attacks sit dormant for long periods of time between the initial entry point (likely through a phish) until the attacker uses the point of entry to exfiltrate data or perform the ransomware attack. This length of time is allowing extra time for the attackers to place back doors, spread their foothold and have a much greater impact on an organisation.

The third major change is related to the significant increase in the percentage of people working from home. We are seeing many ad hoc remote access holes poked into organisations’ firewalls to allow their remote workforce to do their jobs, creating a much larger public facing footprint for organisations. This includes new VPN technology and, unfortunately, a large number of remote desktops listening directly on the Internet.

Attackers are taking advantage of these new paths into an organisation. The simplest path appears to be Windows Remote Desktop (RDP), where the attack simply requires a brute force (repeated login attempts) attack that, after some period of time, a local login credential will gain them access.

We saw this type of attack hit the Bruce T. Haddock Water Treatment Plant in Oldsmar, Florida in February of this year. The attacker found a remote desktop that was added to allow employees to work from home and was connected to an industrial controls system. This allowed the attacker to raise the levels of sodium hydroxide in the water from about 100 parts per million to 11,100 parts per million for a few minutes. While this was caught by the company quickly but shows the significant risk to systems that have not been connected to the Internet in the past and the potential damage that could be done by an attacker.

We expect to see similar risk continue to grow as the Internet of Things (IoT) increases in use as systems become increasingly automated, especially in the manufacturing, energy, and utility sectors, which have a large number of industrial control systems and SCADA networks that can see many business benefits to automation systems using IoT. Many of the IoT devices that are deployed are running simple, embedded operating systems that are not managed by the organisation for patches and updates like typical computer systems, creating potential vulnerabilities and a path into the network through the IoT device.

Overall, the past two years have seen a major increase in attacker activity and sophistication of attack vectors, which are creating a significant increase in cyber risk for many companies.

In recent months, major cyber-attacks against infrastructure assets in the U.S. have had unprecedented impacts on the economy, what could have been done to prevent this?

These attacks are different from what has been seen in the past and, therefore, many organisations weren’t prepared to quickly identify and respond to them.

There are a number of changes needed to ensure improved protection against these types of attacks. The first is a defence in depth strategy. This is not a new term but is even more critical today than it has ever been. We have to assume we will be attacked and build controls to identify anomalous activity in our environment, along with alerts inside the network just as we typically have at the perimeter. No longer can the perimeter be the end of security control. This has been a topic for over 20 years, but many organisations continue to be missing basic controls. If we assume that an employee will click a link in a phishing email at some point, allowing an attacker access inside the firewall through their machine, then we must not rely on the firewall to protect us. These internal controls start with endpoint detection and response (EDR). Running anti-virus software on endpoints is no longer acceptable, EDR software allows automated action against many types of attack and, when centrally monitored, can be utilised to quickly isolate an infected machine to reduce the impact of an attack.

In addition, there are many other technologies and services that can help prevent, or reduce the impact of, attacks like we have seen over the past two years, including Managed Detection and Response (MDR), Security Information and Event Monitoring (SIEM), Data Loss Prevention (DLP), data encryption (file, database, transport), and email filtering. The second, and possibly even more critical, action that would have reduced the impact of these incidents is a well planned and tested incident response plan. We have to assume an attack will happen and, as such, we should be prepared to respond when it does. This includes knowing how to identify and escalate an incident, who performs what actions, when to alert outside parties (incident response firm, state/federal authorities, customers, employees), and how to handle communications.

Running tabletop tests to ensure the responding team is familiar with these actions and practices how to respond will allow a more organised and calm approach when a real incident occurs. These tests also allow improvements to be made to the response plan to ensure a smooth process. Too many organisations make major mistakes that, if planned out, could have allowed much quicker action and a coordinated response when an incident occurs.

The third mitigation control is a backup and recovery plan. Implementing a good backup strategy with disconnected backups can minimise the risk of an attack impacting your backups. These backup plans should be regularly tested to ensure recovery is possible from various forms of attack. In addition, a Business Continuity Plan (BCP) should be developed to ensure the organisation can perform basic activities without the use of computer systems while restoration is being performed. If organisations have a good backup and recovery plan, there is no need to pay a ransomware attacker for a key that is unlikely to even work. The organisation can utilise its incident response plan to take action to stop the attack and at the same time kick off their recovery plan to bring the business back to normal operations while using the continuity plan to keep it running while in an impacted state.

We always talk about aging infrastructure, referring to these invisible pipes and mains underground, but there are far more quickly aging invisible assets in IT. Which ones are particularly of concern?

The impact of closed systems that are now being exposed through advances in technology such as IoT and remote workforce access are exposing aging industrial control systems that in the past had never been exposed. This risk exists even if these systems are not on the public Internet but instead being added to the internal company network to allow remote control, data collection or automation of systems.

These systems are often running on old hardware with embedded operating systems unable to be patched or maintained. Any changes made to the environment creating connection points from more modern network systems to an industrial control network should come with a risk assessment of the environment to ensure appropriate controls have been implemented with the new technology. The business gains may outweigh the risk generated, however appropriate controls can be implemented to minimise the risk and impact to older IT systems.

For more ways in which utility managers and owners can address cyber threats for critical infrastructure, see here.

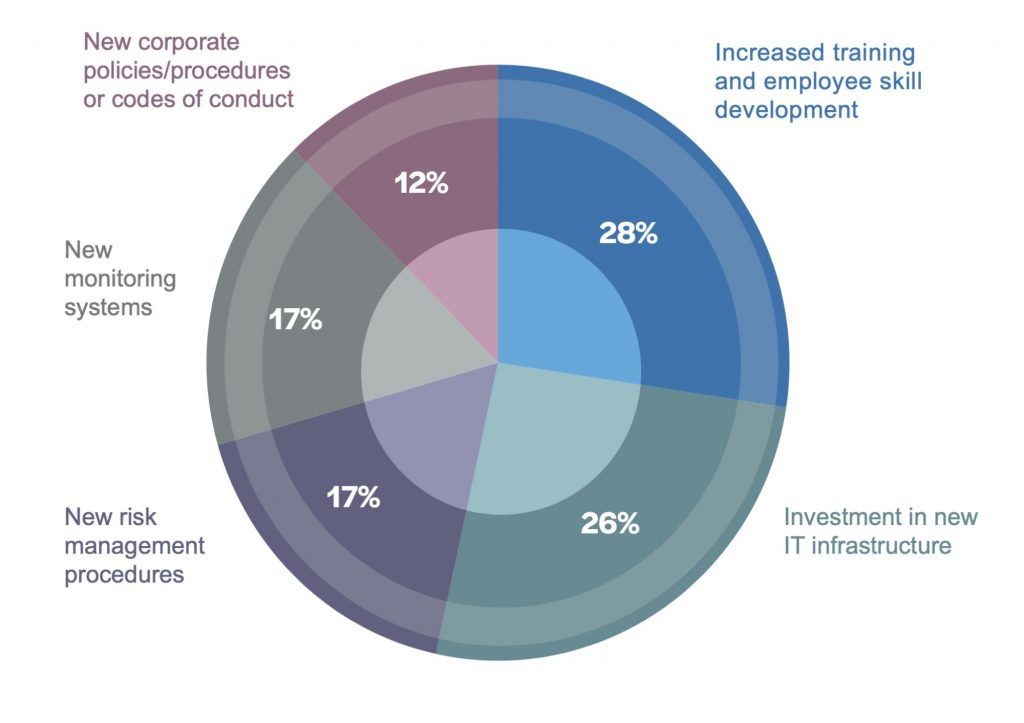

Figure 1 – Which additional measures or corporate practices do you believe are most effective at mitigating IT security risk?

The cost of compliance and the required investments in cybersecurity/data privacy are increasing. Is funding easily available for smaller companies or utilities?

I have not seen much easy access to funding to assist small companies or utilities with cyber investments. However, after the Colonial Pipeline attack, the federal government issued new legislation to define control frameworks to follow, with recommendations on implementing better controls. I expect to see additional grants or funding opportunities coming out of these continued attacks.

Unfortunately, it often takes major incidents with an impact on the country to drive this assistance. The Colonial Pipeline attack did appear to create a significant improvement in awareness of the potential damage when a major fuel pipeline is shut down, which should result in improved assistance to implement security controls on critical infrastructure and utilities.

The Mazars US Water Industry Outlook is based on a 26-question survey that was conducted in 2020/2021. You can find all the survey results and read the full report here.