Covid-19: emerging trends on the availability and cost of infra debt

Covid-19: emerging trends on the availability and cost of infra debt

In a previous article, I wrote about the early impact of Covid-19 on equity valuations across the energy and infrastructure space, noting changing cashflow expectations in some sectors, but not necessarily all, and no general trend of higher discount rates.

I will provide an update of valuation trends in a future piece, but in this article want to switch attention to some pricing and other trends in the private debt space since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Some brief pre-Covid context first. In the period leading up to March 2020, debt margins were low by historical standards, and getting lower – towards levels last seen before the financial crisis of 2008. When combined with historically low swap rates and the widespread availability of favourable commercial terms from lenders, this was driving a significant amount of refinancing activity. In December alone, this added up to at least 80 deals globally, and well over $20bn of debt raised, including $15bn+ from commercial loan instruments.

Transaction volumes since the onset of Covid-19

So what has happened since then? The story in March was mostly of sponsors seeking to close existing deals. Based on Inframation data, nearly 40 refinancing deals reached financial close that month, adding up to c.$8bn. In terms of number of transactions reaching financial close, this actually compares closely to March 2019.

But in April, the number of closed transactions fell sharply – just 12 refinancing deals globally. In May, the equivalent figure was just over 20 deals reaching financial close. These levels of transaction volumes equate to roughly half the equivalent period in 2019, and are much lower also than the average of 40 deals per month reaching financial close in the previous 6 months.

Looking at the M&A and greenfield closed transactions which included debt, there is a similar picture. March was a fairly busy month with 30 closed transactions. But in April, this number had gone down to 18, and in May, just 11. There have been over 100 cancelled greenfield and M&A debt transactions in the same period in the public domain. A significant number of these were tied to public authorities cancelling tendering processes, but there were also more than 20 cancelled transport transactions for instance.

Debt pricing and other trends since the onset of Covid-19

Mazars has worked on just over 20 debt financing deals since the start of March, many of which have now reached financial close. We have also received multiple term sheets from lenders across sectors tied to prospective deals, and had conversations with others.

Our main conclusions from this are as follows:

- No wholesale pulling of plugs or renegotiation. For nearly all existing deals nearing financial close at the onset of Covid-19, lenders were able to honour agreed terms. We saw very few lenders pulling out of deals at that stage. It was also not typical for margins to be increased at the last minute prior to financial close (although this did happen in a small number of cases).

- Pricing increases for new deals. Margins have increased, pretty much across the board. In broad terms, this increase has been in the range of 50 to 100bps.

- Some reduction of risk appetite, and associated delays. In addition to this increase in margins, it would appear that some lenders are also becoming more conservative in other ways, including a more cautious approach to sizing criteria, tenor and other terms, as well as being less willing to ‘take a view’ following diligence processes. This has led to some transactions taking longer to execute. At the same time, reduced risk appetite is only going so far – for instance, we are continuing to see lenders offer Debt Service Reserve Facilities as opposed to requiring Debt Service Reserve Accounts.

- A reduction in debt capacity. Some lenders are retrenching to key relationships or core markets. And lenders are generally less willing to take on underwriting risk – in other words to take risk on the behaviour of others. So there is generally less debt capacity in the market. (But at the same time, there are fewer deals coming to market.)

So now is not a great time to launch a debt deal, right?

Actually, it might be.

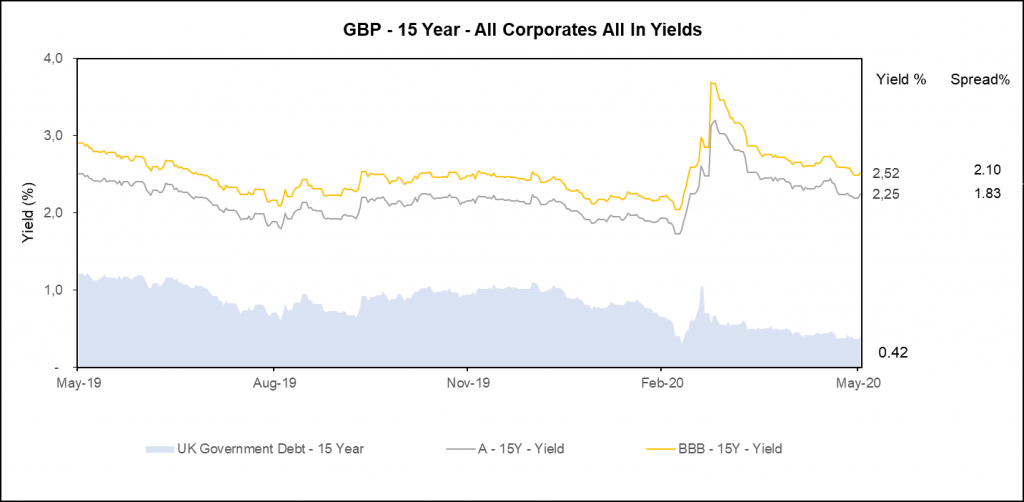

For one thing, whilst margins may have been increasing, swap rates have declined significantly. So the overall cost of debt is not much higher than it was 6 months ago. This trend can be seen clearly when looking at all-in bond pricing, taking 15 year pricing as an example:

Yes, current spreads are higher vs 12 months ago, but actually the total cost of debt is lower overall, and at levels very comparable to last autumn. With private debt pricing not far off these levels – at least for some sectors – from a borrower perspective, a debt deal may still look like an attractive option.

There are other advantages to doing refinancing deals now. In the context of potentially fewer opportunities (or less willingness) to deploy new equity capital, asset managers have time and incentive to focus their attention on optimising existing portfolios. For the right deals, and with the right lender, there will be strong appetite and capacity all round to focus on driving the deal towards financial close.

The one big caveat to this though is that much will depend on deal fundamentals – which may look different from sector to sector.

Projects with stability and relative certainty of assumptions such as social infrastructure assets with availability revenues or renewable energy assets where a short-term power price reduction doesn’t change their fundamental risk profile will see strong appetite and be able to achieve good levels of gearing and tenor.

But in sectors hit most by the impacts of Covid-19, such as toll roads, ports and airports, where projects have revenues linked to demand in the real economy, they will face:

- more deal execution risk, and a

- need to bake in conservative assumptions; as well as

- potentially higher pricing to reflect a perception of higher risk,

Which may mean that sponsors will elect to hold off until later in 2020 or 2021.

A return to 2009?

For all the short-term disruptions, the current picture feels a long way away from the last major financial shock of 2009. Whilst it may be easy to presume a similar outcome (global financial shutdown), it is clear that capital availability has not currently dried up and banks are still willing and able, selectively, to lend.

In 2009, a new market for investment had to be created, specialist infrastructure loan funds, to fill a funding gap. This time, there is a real-world crisis but not necessarily a credit crisis (at least yet), and the thesis that the infrastructure and energy sectors ought to be resilient to economic downturns is for now at least partly holding true.